Published on 04/01/2019

The current Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo was declared on the 1st August 2018 and has grown to become the second biggest EVD outbreak to date.

This recent outbreak followed on from the earlier Équateur province Ebola outbreak which occurred May to July 2018.

The West African Ebola virus epidemic was the largest to date with 28,616 reported cases and 11,310 deaths – although it was suspected that 17-70% of cases went unreported.

This epidemic saw reported cases outside of Africa in the United States, United Kingdom, Italy and Spain.

It was believed to have started in December 2013 when a one-year-old boy in Guinea died from the disease. Later, his mother, sister and grandmother died from the same symptoms.

The village was close to a large colony of Angolan free-tailed bats, which have been thought to spread Ebola, yet none of the bats tested were found to carry the disease.

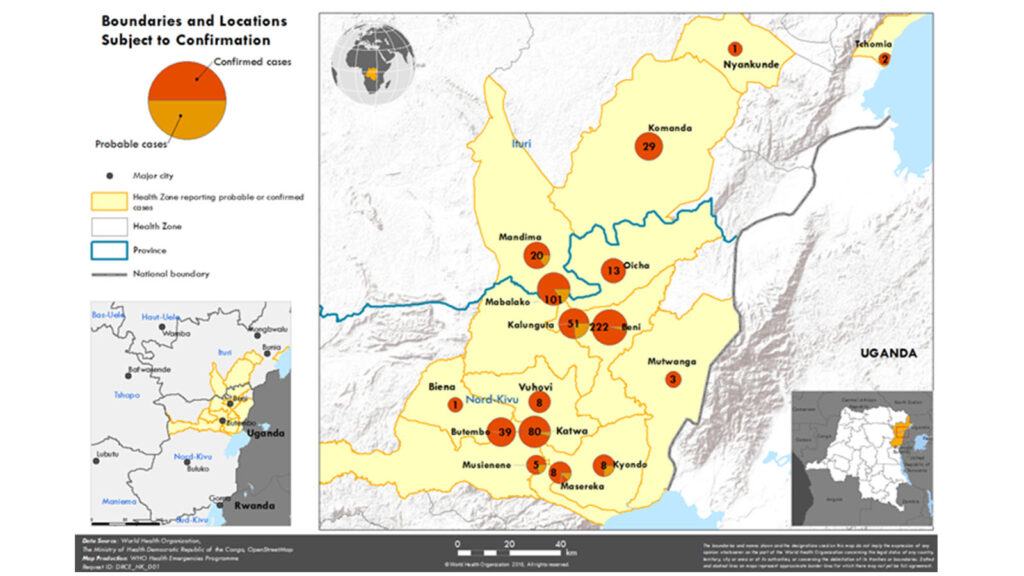

As of 26th December 2018, a total of 591 EVD cases, including 543 confirmed and 48 probable cases, have been reported.

These reported cases have come from 16 health zones in the two neighbouring provinces of North Kivu and Ituri (Figure 1).

Of these cases, 54 were healthcare workers, of which 18 died. Overall, 357 cases have died (case fatality ratio 60%).

In the past week, ten additional patients were discharged from Ebola treatment centres; overall, 203 patients have recovered to date. The highest number of cases were from age group 15‒49 years with 60% (355/589) of the cases, and of those, 228 were female.

WHO advises against any restriction of travel and trade to the Democratic Republic of the Congo based on the currently available information.

Currently, no country has implemented travel measures that significantly interfere with international traffic to and from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Travellers should seek medical advice before travel and should practice good hygiene.

Ebola’s transmitted through close and direct physical contact with infected bodily fluids. The most infectious being vomit, blood, and faeces.

There have also been cases of Ebola detected in breast milk, urine and semen; with studies detecting the virus 70 days after the patience had recovered from symptoms.

There have also been studies showing the virus to be present in Saliva and tears, but the sample size was limited.

If coming into contact with those who may have Ebola, you should ensure protective equipment is worn.

Ebola can be transmitted indirectly through contaminated objects and surfaces.

If you are frequently in contact with objects, materials or surfaces that could carry infection, it’s recommended to regularly clean and disinfect. Wearing protective equipment will decrease the risk of transmission.

There is no evidence that Ebola can be transmitted via airborne means. The virus could be transmitted through large wet droplets from a heavily infected individual coughing and sneezing at close distance, but no study has confirmed this.

Again, if you are in close proximity with people who may be in contact with the virus disease, ensure thorough cleaning procedures are in place and consider safety equipment.

There is currently no licensed vaccine to protect people from the Ebola virus. Therefore, any requirements for certificates of Ebola vaccination are not a reasonable basis for restricting movement across borders or the issuance of visas for passengers leaving the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

The latest Ebola outbreak is the second biggest to date, behind the West African Ebola virus epidemic 2012-2016.

There are currently just short of 600 cases, with around 10% of those being healthcare workers.

Ebola is passed through direct contact with infected bodily fluids and can survive for 70+ days after the symptoms have passed.

Although there is currently no cure, the risk of spread can be greatly reduced though personal and surface cleaning procedures, and further reduced with protective equipment.